A young mother recently asked me if she should worry about her daughter who had just started kindergarten that week. She told me that her child could recognize and name all her letters and was very good with hearing most sounds, but when writing all on her own, she sometimes formed the letters backwards. Her preschool hadn’t done writing at all and so the child’s only experience with writing was playing in some workbooks at home that she enjoyed. Her mom happened to glance at a page where the little girl had filled in the first letters of cow, cat, snake, dog, and so on and more than 70% were written backwards. The mom had heard that reversals are a sign of learning disabilities and she wasn’t sure if she should worry about this or not.

A young mother recently asked me if she should worry about her daughter who had just started kindergarten that week. She told me that her child could recognize and name all her letters and was very good with hearing most sounds, but when writing all on her own, she sometimes formed the letters backwards. Her preschool hadn’t done writing at all and so the child’s only experience with writing was playing in some workbooks at home that she enjoyed. Her mom happened to glance at a page where the little girl had filled in the first letters of cow, cat, snake, dog, and so on and more than 70% were written backwards. The mom had heard that reversals are a sign of learning disabilities and she wasn’t sure if she should worry about this or not.

Writing letters backwards is very normal for many children, but at what point do we put a stop to it and help out? When children are three and four years of age, I don’t interfere. But the kindergarten year is a good year for some intervention. I explained to the mom about many of the things the teacher might be doing throughout the day which would help her daughter start to realize that directionality does matter. Every single day in many of her activities, the K teacher will be modeling writing in front of the students. She’ll be talking about where to start the letter and how to form it as she does interactive writing and shared writing. While the students are creating a real message together the teacher may have them use whiteboards to form some of the letters for practice. There will be so many hundreds of examples presented throughout the day that usually those backward letters will begin to disappear.

Keep in mind that when young children are learning to look at print, this is the first experience where order and directionality matter. Prior to their encounters with print, they are used to recognizing things in their world in various positions. Think about it. There is really no sequential order or direction that matters when viewing a toy car. The child will recognize it whether is it facing forward, backward, or upside down, and it is still a toy car, no matter what position it is in. However, with printed text, such as words and letters, order and direction do matter. A c is only a c when it is facing this way. An s is not an s if it is written backwards. I’m reminded of my own grandchild at 4 1/2 who wrote ‘cta’ on a piece of paper. My husband asked, “What does that say?” She said, “It says ‘cat’.” He told her that it really was only ‘cat’ when the ‘a’ was in the middle. She answered quite confidently, “No Papa, it doesn’t matter, it’s still cat.” She, too, will soon learn that in the printed world, order does matter.

Now a word to kindergarten and first grade teachers. This is the time to support children in learning how to form letters correctly. Does that mean I support 30 minutes of handwriting every day? No. In Chapter 5 of our text, Catching Readers Before They Fall, we talk about the comprehensive framework that we use in our classrooms. Please refer to that to see how Katie, in her primary classrooms, has always included directionality and learning letters and sounds through all sorts of reading and writing activities. If teachers are carefully observing their students during writing times, they can support them in learning ways not only to form letters, but also ways to become independent in checking on themselves. Problems only arise when children are left alone during their kinder and first grade years to make the backward letters over and over and over again. Marie Clay says, “Only careful monitoring will assure me that the child is not becoming confused and practicing inappropriate behaviors…..(A child) may practice behaviors day after day for a year, and that will handicap his subsequent progress.” (Literacy Lessons I, page 11.) Therefore, kindergarten teachers should be constantly observing their writers. It is so much easier to correct directionality issues at this early stage then to let it go and have a 2nd, 3rd, or 4th grade teacher try to ‘undo’ years of backwards letters and words.

I often recommend that K teachers make sure that the child has the letter ‘c’ under control. Why? Because ‘c’ is so useful in forming other letters that often become backward letters. Make an ‘s’ – “It starts like a ‘c’ and then down and around.” Make an ‘a’ – “It starts like a ‘c’ and then up and down.” Make a ‘g’ – “It starts like a ‘c’, then up, and the all the way down with a hook.” So how do we get that ‘c’ solid; going in the right direction? It’s best to stand the child in front of a large white board or chalkboard (making the letter LARGE first is very helpful.) If the child is right-handed, have her place her left hand, palm down on the board. With the marker or chalk in her right hand, have her say, “towards my hand, ‘c'” as she is making the letter. (Reverse, if the child is left-handed, saying, “Away from my hand, ‘c’.”)

One last tip. What about the famous b/d reversals? I teach how to form these letters in two different ways. When you teach both by starting with the stick, the child gets confused as to which side to put the ball on. I teach ‘b’ by doing the stick first and then the ball, but then I give the child an index card with the capital B on it. The child has to do the self-monitoring. Did I make the ball on the same side as the capital B? He now has a way to check it on his own.

For forming the letter ‘d’, I DON’T have them start with a stick. Instead I teach them to “start with a ‘c’ and then add the line.” You can even sing the first four letters of the ABC song…. a, b, c, d (emphasize the letters c and d) as you form the letter ‘d’.

Hope this all makes sense. It’s a lot easier to explain to someone who is right in front of me than to write it down. The whole point is that for this particular mom it was too early to worry. Her daughter seemed to be doing fine in all other aspects of literacy; she just had had little experience with writing. Hopefully with a strong kindergarten experience, the problem will take care of itself. If, however, a teacher or parent finds the problems persist to the end of kindergarten and into first grade, you may want to try some of the activities on pages 117-119 of our text. These would only be necessary in rare cases.

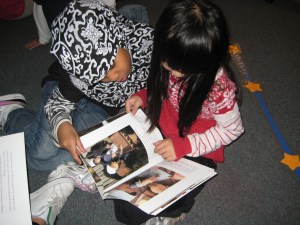

Friday was the 9th day of school – and the 9th day of Writer’s Workshop in our kindergarten classroom. We make books every day after lunch, a routine that was established on the very first day of school. Our Writer’s Workshop begins by reading or revisiting a book and talking about the author. I introduced David Shannon as the first author we studied. We read No, David! and I shared the author’s note on the inside cover where David talks about how he got the idea for this book. I sent my 4 and 5 year olds off with 5 pages of stapled, blank pieces of paper to “make books, just like David Shannon!” Every single one of my kindergarteners then proceeded to make a book – and many complained when I called them back to the rug after 30 minutes of writing time. I had to reassure them that we would have time tomorrow and every day to write. We shared our books then – princess books, dinosaur books, truck books, kitten books, cowboy books – all of the children had chosen a different topic and made a book about the topic that was important to them. If I didn’t know better, I would say it was magic.

Friday was the 9th day of school – and the 9th day of Writer’s Workshop in our kindergarten classroom. We make books every day after lunch, a routine that was established on the very first day of school. Our Writer’s Workshop begins by reading or revisiting a book and talking about the author. I introduced David Shannon as the first author we studied. We read No, David! and I shared the author’s note on the inside cover where David talks about how he got the idea for this book. I sent my 4 and 5 year olds off with 5 pages of stapled, blank pieces of paper to “make books, just like David Shannon!” Every single one of my kindergarteners then proceeded to make a book – and many complained when I called them back to the rug after 30 minutes of writing time. I had to reassure them that we would have time tomorrow and every day to write. We shared our books then – princess books, dinosaur books, truck books, kitten books, cowboy books – all of the children had chosen a different topic and made a book about the topic that was important to them. If I didn’t know better, I would say it was magic.

![The_Thinker_Rodin-2-713279[1]](https://catchingreaders.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/the_thinker_rodin-2-71327913.jpg?w=288&h=300)